Introduction

The term “late-stage capitalism” has become an omnipresent catchphrase in modern discourse, representing a broad critique of the capitalist system's structural failings. Far beyond its beginnings in Karl Marx’s seminal critiques and Werner Sombart’s delineation of capitalism's phases, the term now encapsulates a sense of impending systemic collapse marked by extreme inequality, ecological degradation, and social unrest. The current phase of capitalism—characterized by financial speculation, global monopolies, and a pronounced divide between economic classes—presents symptoms that many theorists argue indicate not merely a stage within capitalism but a signal of its terminal decline.

The foundation for understanding why late-stage capitalism appears to be failing is built upon an array of historical, economic, and social analyses. From Marx’s insights on capitalism’s inherent contradictions to Lenin’s theory of imperialism and Ernest Mandel’s analysis of post-war economic expansions, a robust intellectual framework has examined the ways in which capitalism may carry within itself the seeds of its undoing. Each of these perspectives underscores the inevitability of crises within capitalist economies, crises that have grown in scope and severity as capitalism has matured into its current form.

This article seeks to analyze and synthesize these views, focusing on how late-stage capitalism fails to sustain the ideals it claims to uphold—such as individual liberty, economic prosperity, and social mobility. Instead, what emerges is a system increasingly dominated by monopolistic corporations, oligarchic wealth concentration, and government policies that serve to protect capital at the expense of the broader populace. Drawing on interdisciplinary insights and key historical documents, this piece offers a comprehensive exploration of late-stage capitalism’s systemic flaws, presenting a case for why this economic model may be unsustainable in the long term.

Chapter 1: Historical Roots and Theoretical Foundations

Section 1: The Evolution of Capitalism from Proto to Late Stage

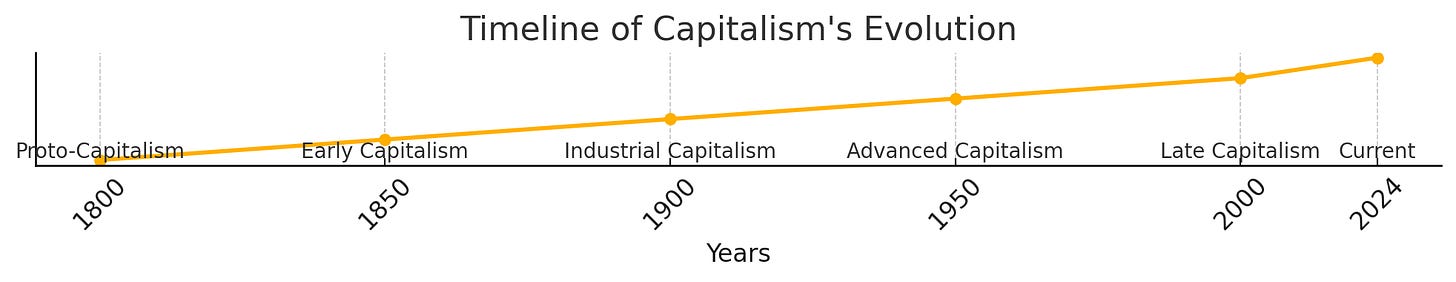

This timeline highlights capitalism's stages, from Proto-Capitalism to Late Capitalism. Werner Sombart introduced this phased model (Sombart, Der moderne Kapitalismus, 1902), later expanded by Karl Marx, who emphasized capitalism’s internal contradictions (Marx, Das Kapital, Volume I, 1867), and Ernest Mandel, who linked the phases to historical and economic crises (Mandel, Late Capitalism, 1978)

The progression of capitalism through various stages has been a central topic in economic thought, beginning with early trade-based and industrial economies and advancing through the imperialist expansion of capitalist interests across the globe. Werner Sombart, an early 20th-century economist, introduced a tripartite framework for understanding capitalism: proto, advanced, and late. Sombart’s analysis marked the latter stage as an epoch marked by substantial economic, political, and social upheavals. It was a phase he argued could no longer sustain itself through traditional means of growth, reflecting both the exhaustion of new markets and the deepening of internal contradictions.

Sombart’s framework, later built upon by Marxist thinkers such as Lenin and Mandel, suggested that as capitalism matured, it would face increasingly insurmountable crises. For example, Marx foresaw that capitalism’s emphasis on competition would eventually drive markets to monopolistic extremes. This monopolization, rather than fostering innovation and competition, would instead result in stagnation as the dominant firms in each industry gained disproportionate control over prices, wages, and policies that would typically enable free-market dynamics. Lenin, in his work Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, furthered this analysis by linking the expansion of monopoly power to global imperialism, wherein advanced capitalist states would exploit developing nations as a means of countering domestic stagnation.

Ernest Mandel’s mid-20th century work, Late Capitalism, reinterpreted these ideas in light of post-World War II economic phenomena. Mandel argued that the economic boom following the war was atypical and ultimately unsustainable, driven by factors such as increased public spending, the growth of multinational corporations, and the expansion of credit systems. According to Mandel, these factors temporarily postponed but did not eliminate capitalism’s inherent contradictions, setting the stage for the crises of the 1970s and the subsequent neoliberal transformations that define today’s economic order.

Section 2: Shifts in Economic Focus: From Production to Finance and Speculation

In the transition from early industrial capitalism to today’s financialized economy, the fundamental drivers of wealth creation have shifted. Traditional industries that focused on producing goods have been largely overshadowed by financial markets, where wealth is generated through speculation rather than tangible production. This evolution has had profound effects on the structure of capitalism, steering it away from its initial focus on productive labor and into an era of speculative gains that benefit a small percentage of society.

By the 1980s, neoliberal policies promoted deregulation and encouraged the expansion of global finance, shifting wealth creation to speculative investments in stocks, bonds, and derivatives. The rise of these financial instruments has allowed corporations and the ultra-wealthy to accumulate unprecedented fortunes, often at the expense of economic stability for the general population. This shift toward finance and speculation has concentrated wealth among a small elite, resulting in what some describe as the emergence of a new “American oligarchy”.

The consequences of this shift are significant. By diverting resources away from productive investments, late-stage capitalism has weakened the broader economy, limiting job growth and wage increases for the majority. This era of financialization, rather than providing widespread prosperity, has exacerbated inequality and led to economic instability. The 2008 financial crisis serves as a stark example of the vulnerabilities inherent in a financialized economy, where the pursuit of speculative profits for a few can lead to systemic failures that affect millions.

Section 3: Monopoly, Financialization, and Inequality

This graph demonstrates the increase in income share held by the top 1%, reflecting capitalist tendencies toward wealth concentration and monopolization. It aligns with Marx’s and Lenin’s analyses of monopolistic forces within capitalism and modern interpretations by Jason Hickel, who highlights the widening income gap as capitalism matures (Piketty, Capital in the Twenty-First Century, 2014; Hickel, Less Is More: How Degrowth Will Save the World, 2020)

One of the defining characteristics of late-stage capitalism is the rise of monopolies and oligopolies. Traditional capitalist theories, particularly those rooted in the works of Adam Smith and early economic theorists, espoused the idea that free markets, characterized by competition among many small businesses, would yield the greatest benefits for society. However, as capitalism matured, competition led not to a proliferation of businesses, but to consolidation within industries. Large corporations, equipped with immense financial and political power, increasingly absorbed or eliminated competitors, establishing monopolistic or oligopolistic control over key economic sectors. This concentration of power fundamentally altered the landscape of capitalism, shifting it away from the free-market ideals that initially justified its structure.

Marx’s early predictions on the centralization of capital are particularly prescient here. In Capital, Marx argued that as capital accumulates, a select group of businesses would come to dominate, creating monopolies that suppress wages, exploit labor, and distort market dynamics. This trend is starkly evident today, particularly in sectors such as technology, pharmaceuticals, and finance, where a handful of multinational corporations wield immense influence over global markets. This monopoly power has profound consequences: it curtails innovation, restricts consumer choice, and places economic and political power into the hands of a wealthy elite.

Financialization, another hallmark of late-stage capitalism, has exacerbated these issues. As mentioned earlier, the shift from production to finance has restructured economies in ways that prioritize speculative investments over tangible production, often leading to cycles of boom and bust. Rather than investing profits back into productive assets or increasing wages for workers, corporations in a financialized economy are incentivized to engage in stock buybacks, mergers, and other practices that inflate stock prices without creating real value. This practice, criticized by economists as a form of “value extraction” rather than “value creation,” reinforces wealth inequality by channeling profits to shareholders and executives rather than to the workers who generate those profits.

Moreover, the emphasis on financialization has led to the emergence of what some theorists refer to as a new “financial aristocracy.” Lenin’s analysis of the financial oligarchy in Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism identifies the rise of a powerful class of financiers whose wealth and influence far exceed that of the general population. This phenomenon has only intensified in the late 20th and early 21st centuries. The financial crises of recent decades—including the 2008 global financial crisis—highlight the fragility of an economy built on speculative investments and underscore how the financial sector’s risks disproportionately impact working-class populations.

These dynamics contribute directly to a widening wealth gap and increasing social inequality, evident both within countries and globally. According to recent studies, the top 1% of income earners now control an unprecedented share of global wealth, while wages for the bottom 90% have stagnated. In the United States, for example, real wages have barely kept up with inflation since the 1970s, even as productivity has increased dramatically. This disparity illustrates a core failure of late-stage capitalism: its inability to provide equitable economic benefits, a promise that formed the ideological foundation of capitalist societies but has become increasingly unattainable.

Chapter 2: The Socioeconomic Manifestations of Decline

With a firm historical and theoretical foundation established, Chapter 2 transitions into examining the specific socioeconomic impacts that characterize the decline of late-stage capitalism. This chapter addresses wage stagnation, class stratification, and rising debt, analyzing how these factors manifest within and across societies.

Section 1: Stagnation and Declining Real Wages

This chart shows the divergence between productivity and real wages, illustrating how technological advancements and deregulation have not benefited workers proportionally. Since the 1970s, wage stagnation has become a significant issue in advanced capitalist economies, as noted by economists in World Development studies (Mishel & Bivens, Understanding the Historic Divergence Between Productivity and a Typical Worker’s Pay, 2015; Stiglitz, The Price of Inequality, 2012).

A hallmark failure of late-stage capitalism is its inability to sustain meaningful wage growth for the vast majority of workers. While productivity has consistently increased, especially in high-income countries, real wages for the majority of the population have remained stagnant. This stagnation can be traced back to several economic shifts, including the rise of automation, offshoring of labor, and the weakening of labor unions—factors that, while profitable for corporations, have reduced bargaining power for workers. As a result, despite advances in technology and productivity, workers find themselves unable to afford a standard of living comparable to previous generations.

Historical comparisons indicate that prior to the current phase of capitalism, wage growth typically paralleled productivity gains. In the mid-20th century, wage increases were a natural outcome of economic growth, reflecting the benefits of collective bargaining and higher rates of unionization. However, since the 1970s, policies favoring deregulation and weakening labor protections have shifted the balance of power within labor markets. The consequence is a paradox within capitalist societies: economic growth exists, but its benefits accrue primarily to capital holders rather than to workers. This reality illustrates the failure of capitalism to fulfill its promise of shared prosperity, suggesting that its current structure may be unsustainable.

Section 2: Class Stratification and the Rise of Oligarchy

Another defining feature of late-stage capitalism is the entrenchment of a class-based hierarchy that severely limits social mobility. The growth of economic inequality, fueled by the forces of monopoly and financialization, has created a distinct oligarchic class that possesses disproportionate economic and political influence. This class structure perpetuates itself through generational wealth transfers, exclusive educational opportunities, and connections within elite circles that are largely inaccessible to the general population.

The concept of oligarchy—rule by the wealthy—has taken on new relevance in modern capitalist societies. In the United States, wealth and political influence have become increasingly concentrated among a small group of billionaire families and corporations. This elite class exerts significant influence over political decisions, lobbying for policies that favor their interests at the expense of the broader population. Bernie Sanders and others have drawn attention to the phenomenon of American oligarchs, noting that wealth concentration is eroding democratic principles by allowing the wealthy to disproportionately shape policy outcomes.

Internationally, the implications of this oligarchic control are stark. Wealth concentration within capitalist systems leads to a global class of wealthy elites who maintain power through transnational networks of corporations, investment funds, and financial institutions. This global elite, often shielded by legal protections and tax havens, wields immense power over economies and governments alike. The global South, in particular, continues to experience economic exploitation as multinational corporations extract resources and labor while contributing minimally to local economies. This form of neo-imperialism perpetuates historical patterns of inequality, further entrenching economic disparities on a global scale.

Section 3: The Growth of Debt and Financial Insecurity

This graph highlights rising debt levels across sectors, signifying the financialization of the economy—a trend documented in Mandel’s work on late capitalism. This reliance on debt to fuel economic activity is symptomatic of a financialized capitalist system, which, as Braudel and Mandel noted, prioritizes speculative gains over productive investment (Mandel, Late Capitalism, 1978; Braudel, The Wheels of Commerce: Civilization and Capitalism 15th-18th Century, Volume II, 1982).

In addition to wage stagnation and rising inequality, late-stage capitalism has spurred an era of unprecedented debt accumulation. Individuals, corporations, and governments alike find themselves increasingly reliant on credit to maintain even basic standards of living. For many households, debt has become an inescapable burden, driven by rising costs of housing, healthcare, and education, all of which have significantly outpaced wage growth. The rise of “debt-financed consumption” is a symptom of an economic system that fails to meet basic needs through equitable wage distribution, forcing individuals to rely on credit to bridge the gap between income and expenses.

The 2008 financial crisis brought global attention to the risks associated with debt-driven economies. In the United States, predatory lending practices and subprime mortgages led to a housing market collapse that devastated millions of households. Despite the reforms that followed, the structural issues remain. Today, student debt, medical debt, and housing debt continue to undermine financial security for millions, particularly within younger generations who have inherited an economy of stagnating wages and skyrocketing living costs.

Corporations and governments are not immune to this debt dependency. In a bid to sustain growth, governments routinely increase public debt, often without addressing the root causes of economic instability. Meanwhile, corporations leverage debt to finance stock buybacks, mergers, and acquisitions, prioritizing shareholder returns over long-term stability. This reliance on debt creates systemic risks, as defaults at any level—personal, corporate, or governmental—can trigger broader economic crises. Consequently, the debt-driven model of late-stage capitalism represents a fundamental failure to build sustainable economic foundations, indicating that the current system may not be viable in the long term.

Chapter 3: The Crisis of Public Welfare and Economic Externalities

Section 1: Environmental Degradation and the Climate Crisis

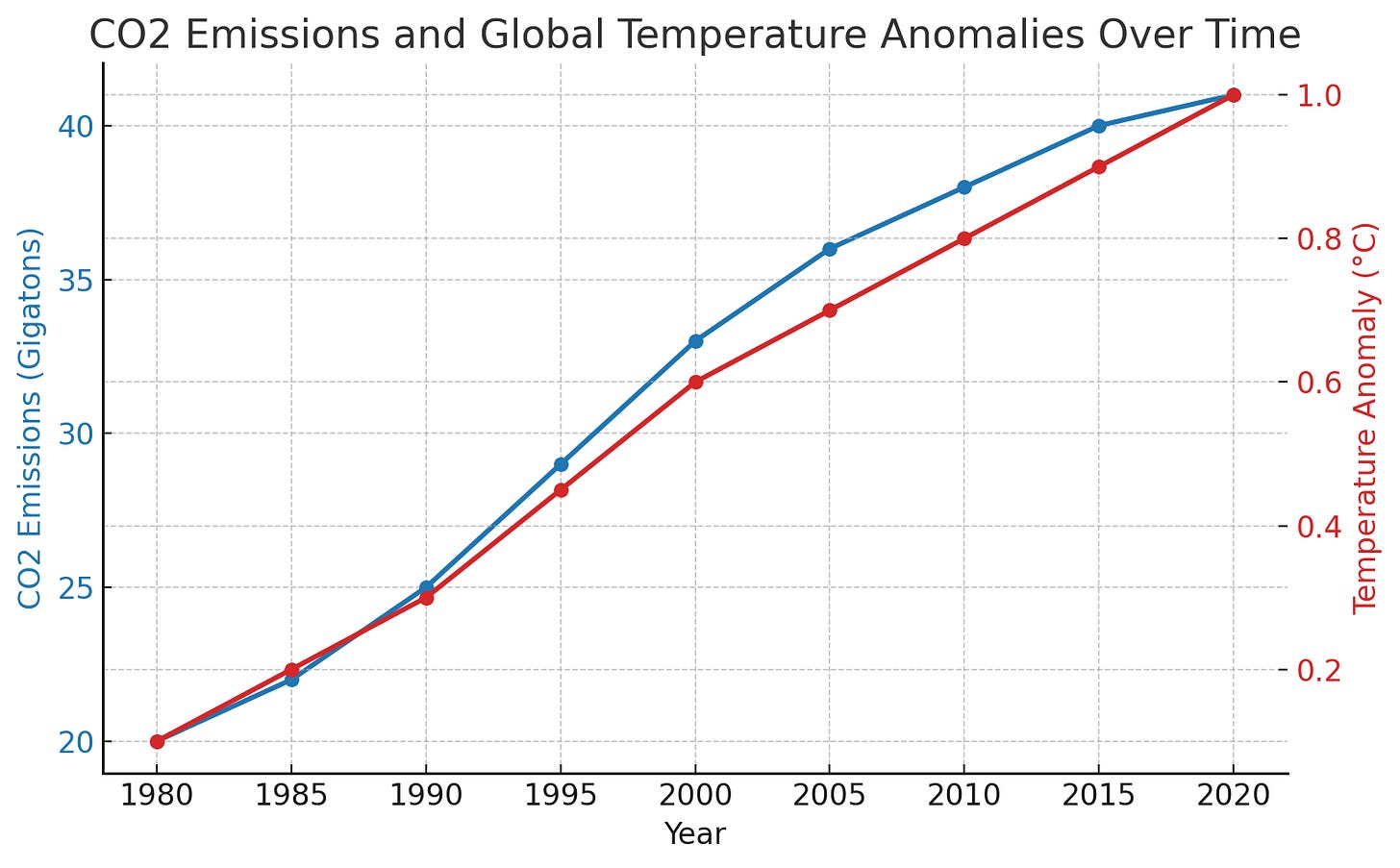

This chart correlates CO2 emissions with global temperature rises, illustrating capitalism’s environmental impact. Scholars such as Hickel and ecological economists argue that capitalism’s growth imperative drives unsustainable resource extraction, significantly contributing to climate change (Hickel & Kallis, Is Green Growth Possible? New Political Economy, 2019; IPCC, Climate Change 2021: The Physical Science Basis).

One of the most severe consequences of late-stage capitalism is its contribution to environmental degradation and climate change. Capitalism’s growth imperative, driven by profit maximization and continuous expansion, has led to unsustainable exploitation of natural resources. Industries under capitalist economies prioritize short-term profits, often disregarding the environmental costs of their operations. This approach has led to widespread deforestation, pollution, loss of biodiversity, and a marked increase in greenhouse gas emissions, all of which contribute to the accelerating climate crisis.

Historically, capitalism’s expansion into global markets relied on exploiting natural resources without accountability. From the colonial period’s resource extraction to the industrial and post-industrial eras, capitalist enterprises have externalized the environmental costs of production, leaving ecosystems and local populations to bear the brunt. This form of “environmental colonialism” persists today, as developed nations outsource pollution-heavy industries to the global South, where environmental regulations are often weaker. Such practices illustrate the capitalist system’s disregard for long-term ecological sustainability, as economic activities are continually prioritized over environmental preservation.

The climate crisis poses an existential threat to societies worldwide, disproportionately affecting vulnerable populations who have contributed least to global emissions. In regions susceptible to climate-induced disasters—such as coastal nations facing rising sea levels—capitalism’s focus on profit and growth is a direct threat to survival. The financialization of resources, such as water, and the commodification of land and biodiversity further exacerbate these inequalities, as corporations acquire control over essential resources, reducing access for local communities. Critics argue that addressing the climate crisis requires systemic changes that capitalism, with its inherent drive for consumption and growth, cannot support. This suggests that solutions to environmental issues may be incompatible with the capitalist model itself.

Section 2: Healthcare and Public Services Under Capitalist Pressure

Capitalism’s profit-driven framework has similarly affected public welfare services, particularly healthcare. In many capitalist societies, healthcare systems have increasingly shifted toward privatization, prioritizing profit over accessible and equitable care. This shift has resulted in healthcare systems that operate as markets, where services are offered based on ability to pay rather than medical need. The United States provides a stark example: healthcare costs have risen dramatically, yet millions remain uninsured or underinsured, unable to access necessary treatments without incurring significant debt.

This issue reflects a broader trend within late-stage capitalism where essential services, from education to housing, are increasingly commodified. As governments reduce funding for public services, private companies step in, often with limited accountability and a focus on profit. In healthcare, this approach has led to inflated costs for medications, medical procedures, and insurance, with prices driven more by corporate profit motives than by the actual cost of care. Meanwhile, health outcomes remain worse for low-income populations and people of color, who face higher barriers to accessing high-quality medical services.

Additionally, the COVID-19 pandemic exposed the vulnerabilities of capitalist healthcare systems. Hospitals worldwide struggled to manage resources effectively, with shortages in essential supplies such as ventilators, protective equipment, and even beds. In many cases, private companies failed to meet public health needs, while governments prioritized economic interests over public health, allowing corporate profit to overshadow humanitarian considerations. This crisis underscores the limitations of a privatized approach to public welfare and highlights capitalism’s incompatibility with the comprehensive provision of essential services.

Section 3: Global Inequality and Exploitation

This graph shows income disparity between developed and developing nations, underscoring how capitalist practices perpetuate global inequality. The income gap aligns with neo-colonial theories by Lenin and modern critiques by scholars like Jason Hickel, who emphasize the extraction-based relationship between developed and developing economies (Lenin, Imperialism: The Highest Stage of Capitalism, 1917; Hickel, The Divide: A Brief Guide to Global Inequality and its Solutions, 2017).

Late-stage capitalism has exacerbated global inequality, perpetuating a cycle of exploitation that leaves developing nations in a continuous state of dependency. Historically, capitalist economies relied on colonial exploitation to fuel their growth, extracting resources, labor, and wealth from colonized regions. Although formal colonialism has largely ended, neo-colonial economic structures persist through mechanisms such as debt, trade imbalances, and multinational corporations that continue to extract resources from developing countries while contributing minimally to local economies.

The extraction of wealth from the global South to the global North is a hallmark of modern imperialism, as theorized by Lenin and later scholars of neo-colonialism. In today’s global economy, multinational corporations wield immense power over developing nations, often operating in ways that mirror colonial practices. Corporations from wealthy nations extract resources—such as minerals, fossil fuels, and agricultural products—while paying minimal wages to local workers, providing little economic benefit to the host country. This system ensures that the global South remains dependent on foreign investment and trade agreements that disproportionately benefit wealthy nations.

Furthermore, global inequality is reinforced through international financial institutions like the International Monetary Fund (IMF) and the World Bank, which impose structural adjustment policies on indebted nations. These policies, often requiring austerity measures and market liberalization, limit government spending on social programs, infrastructure, and public services, thereby exacerbating poverty and inequality. The result is a continuous cycle of dependency, in which developing nations are perpetually indebted and unable to achieve self-sufficiency. This system of global inequality is not a byproduct but rather a feature of late-stage capitalism, which relies on the underdevelopment of certain regions to sustain growth in others.

Chapter 4: Political and Ideological Implications of Late-Stage Capitalism

In Chapter 4, the analysis shifts toward the political and ideological dimensions of late-stage capitalism. This chapter examines how the failures of the capitalist model lead to authoritarianism, populism, and cultural crises that further destabilize societies, highlighting the ways in which political responses to capitalism’s shortcomings exacerbate existing issues.

Section 1: The Shift to Fascism and Authoritarianism as Crisis Management

Late-stage capitalism, with its deep-seated economic inequalities and social fractures, often necessitates authoritarian measures to maintain order. As capitalist economies struggle to address widespread discontent, they may turn to authoritarianism, either explicitly or through subtle shifts in governance, to suppress dissent and maintain the status quo. This phenomenon was historically analyzed by thinkers like R. Palme Dutt, who argued that fascism arises as a response to capitalism’s crisis, enabling the ruling class to consolidate power through coercive means.

In capitalist societies, the preservation of economic stability often comes at the expense of democratic principles. Measures such as surveillance, militarization of the police, and suppression of workers’ rights are increasingly employed to maintain control over populations facing economic hardship. These actions reflect a shift from democratic governance toward authoritarianism, as ruling elites employ force to address the symptoms of capitalism’s failures rather than addressing the underlying structural issues. Fascism, in particular, has been described as a “solution” to capitalism’s inherent contradictions, serving to unite the state and corporate interests in a way that reinforces authoritarian power structures.

Section 2: Rise of Populism and Political Polarization

The graph highlights the rise of populist support, reflecting economic dissatisfaction tied to capitalist structures. Scholars such as R. Palme Dutt have analyzed the shift toward authoritarianism and populism as a response to economic hardship in capitalist societies (Dutt, Fascism and Social Revolution, 1934; Norris & Inglehart, Cultural Backlash: Trump, Brexit, and Authoritarian Populism, 2019).

In addition to authoritarianism, late-stage capitalism has contributed to the rise of populism and political polarization. As traditional economic structures fail to provide for the majority, disenfranchised populations gravitate toward populist movements that promise to address their grievances. Populist leaders often exploit economic discontent, using rhetoric that blames elites, immigrants, or marginalized groups for economic hardship. This polarization serves to fracture societies, making it difficult to build consensus around meaningful reforms that could address systemic issues.

Populism’s appeal lies in its ability to channel frustration with the status quo, offering a sense of empowerment to those who feel left behind by capitalist policies. However, populism rarely addresses the root causes of economic inequality, focusing instead on symptoms. Populist movements on the right often support regressive economic policies that reinforce existing inequalities, while those on the left may propose reforms that lack the systemic overhaul necessary to create sustainable change. In either case, populism thrives on the failures of capitalism, amplifying political division and preventing collaborative efforts to address the deeper issues within the economic system.

Section 3: The Cultural and Social Crises of Late Capitalism

Finally, the cultural implications of late-stage capitalism manifest in widespread societal disillusionment and alienation. The commodification of everyday life, driven by capitalist consumer culture, has led to a sense of disconnection, as individuals increasingly find themselves defined by their economic roles and consumption habits rather than by genuine community and human connection. This commodification extends into nearly every facet of life, from education and health to relationships and personal identity, creating what some theorists describe as an existential crisis within capitalist societies.

Social media, marketing, and the rise of “surveillance capitalism” exacerbate these issues by turning individuals into data commodities, their habits and preferences meticulously tracked to feed consumption cycles. The result is a hyper-commercialized society where human relationships and experiences are mediated by technology and stripped of authenticity. Late capitalism’s focus on individualism and self-interest further isolates individuals, eroding community bonds and contributing to a pervasive sense of alienation. These cultural crises highlight capitalism’s failure to foster genuine well-being, as the pursuit of profit comes at the expense of human connection and fulfillment.

Chapter 5: The Future Beyond Capitalism

Section 1: Potential Pathways and Alternatives to Capitalism

As late-stage capitalism exhibits increasing signs of failure, theorists and activists alike propose a variety of alternative systems aimed at addressing the systemic issues discussed. Chief among these alternatives are socialism, eco-socialism, and other models that emphasize communal ownership, environmental sustainability, and equitable wealth distribution. These systems envision economies where profit maximization is replaced by the pursuit of human well-being and ecological balance.

Socialism has long been regarded as capitalism’s primary ideological and economic counterpoint. Under socialism, the means of production are commonly owned or controlled by the state, and economic planning is intended to serve the needs of the populace rather than private interests. Socialism posits that by redistributing wealth and resources more equitably, societies can alleviate poverty, reduce inequality, and create economic stability. Unlike capitalism, where individual profit motives drive production and innovation, socialism is designed to align production with societal needs, theoretically reducing waste, resource depletion, and exploitation. Historical examples of socialism, however, reveal both successes and limitations; critics point to inefficiencies in central planning and the potential for authoritarian governance, while proponents argue that a modernized, democratic socialism could better address these issues.

Eco-socialism extends the socialist framework to encompass ecological concerns, recognizing that addressing climate change and environmental degradation requires systemic change that capitalism cannot provide. Eco-socialism envisions an economy where environmental sustainability is integrated into every aspect of policy and production. By prioritizing local economies, renewable energy, and sustainable practices, eco-socialism aims to reconcile human needs with ecological limits. This model emphasizes degrowth—a planned reduction in consumption and production—as a counterbalance to capitalism’s growth imperative. Degrowth advocates argue that prosperity can be decoupled from consumption, creating economies that prioritize quality of life, community well-being, and environmental health over material accumulation.

Participatory economics (or “parecon”), developed by economist Michael Albert, is another alternative model that emphasizes participatory decision-making in economic planning. Unlike capitalism, where ownership is concentrated and decision-making is top-down, parecon proposes a system of councils in which workers and consumers directly influence economic decisions. The aim is to create a more egalitarian and democratic society where power and resources are distributed equitably, eliminating the hierarchies inherent in capitalism. This model also integrates concepts of balanced job complexes and equitable remuneration, where labor is rewarded based on effort rather than on market demands. Participatory economics provides a practical framework for a society where collective ownership and direct democracy foster social and economic equality, though implementing such a system on a national or global scale would face considerable challenges.

Section 2: Case Studies in Post-Capitalist Systems

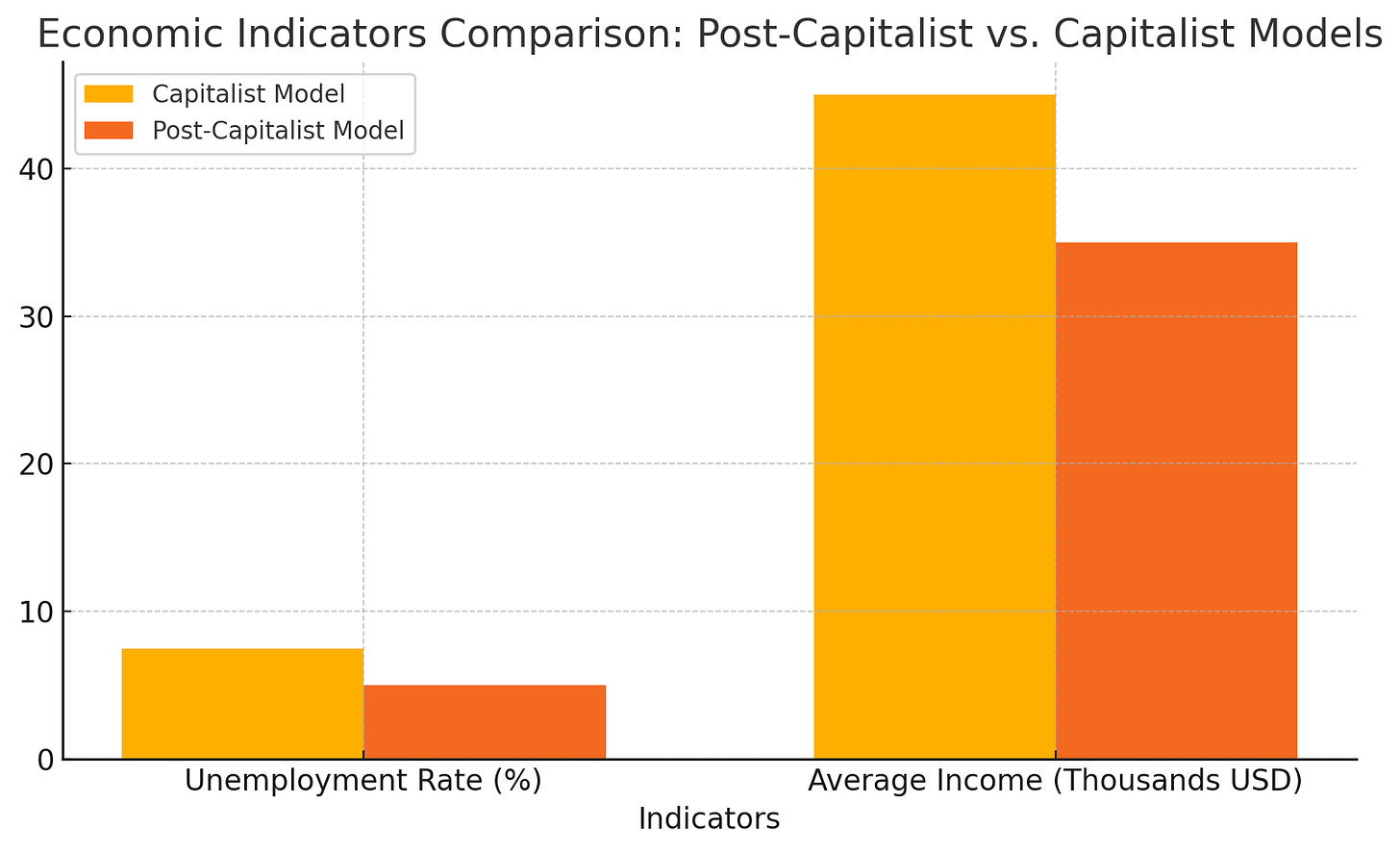

This comparative chart illustrates key economic indicators across different models, suggesting lower unemployment and more equitable income in post-capitalist structures. Studies on cooperative economies, such as Mondragon in Spain, provide real-world examples supporting these observations (Whyte & Whyte, Making Mondragon: The Growth and Dynamics of the Worker Cooperative Complex, 1991; Gibson-Graham, A Postcapitalist Politics, 2006).

Several contemporary case studies offer insights into how alternatives to capitalism might be realized. While no single example provides a comprehensive solution, each demonstrates aspects of post-capitalist thinking in practice, offering lessons for broader adoption.

Mondragon Corporation (Spain): One of the world’s largest worker cooperatives, Mondragon provides a compelling example of an enterprise where workers collectively own and manage the means of production. Founded in the Basque region of Spain, Mondragon operates across various industries and employs over 80,000 workers, all of whom participate in company governance. Mondragon’s structure is based on principles of equity, democracy, and solidarity, with a focus on providing secure employment and sustainable growth. This model challenges traditional capitalist norms by empowering workers and emphasizing long-term stability over short-term profit. Mondragon’s success suggests that worker cooperatives could play a significant role in a post-capitalist economy, particularly in sectors where cooperative ownership aligns with community needs.

Preston Model (United Kingdom): The Preston Model, a form of community wealth-building pioneered in Preston, UK, emphasizes local investment, public ownership, and community control. In response to austerity measures, Preston’s government redirected local spending to support cooperatives, social enterprises, and local businesses. This approach has created jobs, revitalized the local economy, and reduced reliance on private capital. The Preston Model illustrates how local governments can promote economic democracy, reduce dependency on multinational corporations, and foster resilience by investing in their communities. This model of economic localization has the potential to serve as a template for regions seeking to mitigate the impacts of global capitalism on local economies.

Rojava (Syrian Kurdistan): In northeastern Syria, the autonomous region of Rojava has implemented a system of democratic confederalism, inspired by the ideas of Abdullah Öcalan and Murray Bookchin. Rojava’s economy is based on a blend of cooperatives, local councils, and community assemblies, where decision-making is decentralized and inclusive. This system emphasizes gender equality, environmental sustainability, and communal ownership, aiming to establish a society free from hierarchies of class, ethnicity, and gender. Rojava demonstrates the feasibility of an economy based on principles of social and ecological justice, although it faces ongoing challenges due to political instability and limited resources. Rojava’s experience provides a radical vision for a decentralized, non-capitalist society.

Section 3: Policy Proposals and The Road to Transition

While these case studies offer inspiring examples, transitioning to a post-capitalist society on a global scale would require significant systemic changes. Several policy proposals could serve as stepping stones, encouraging a gradual shift away from the capitalist model and fostering conditions for more equitable and sustainable economies.

Universal Basic Income (UBI): UBI has gained traction as a policy that could alleviate poverty, reduce economic inequality, and empower individuals by providing a guaranteed income independent of employment. UBI addresses one of capitalism’s central issues—income insecurity—by decoupling income from labor. This policy would enable people to pursue non-economic activities, reduce dependency on exploitative jobs, and stabilize economies by providing a consistent consumer base. However, UBI alone may not be sufficient to address the broader structural issues within capitalism, and it would need to be part of a broader strategy to ensure it does not merely support consumption without addressing production.

Wealth Taxes and Corporate Accountability: Taxing the wealthiest individuals and corporations more heavily could address income inequality, fund social programs, and redistribute wealth within capitalist economies. By implementing wealth taxes and closing tax loopholes that benefit the ultra-wealthy, governments could curb oligarchic power and provide the resources necessary for essential services. Additionally, enforcing stricter regulations on corporations—such as carbon taxes, labor rights protections, and financial transparency requirements—could reduce exploitative practices and incentivize sustainable business models.

Green New Deal (GND): The Green New Deal, championed by progressive leaders globally, aims to transition economies toward renewable energy, sustainable agriculture, and environmentally-friendly infrastructure. The GND represents a fundamental shift away from capitalism’s extractive approach, seeking to create green jobs, reduce carbon emissions, and address social injustices. A Green New Deal would require massive public investment, a reorientation of energy policies, and a commitment to social equity, making it a comprehensive approach to both environmental and economic issues. While ambitious, the GND aligns closely with eco-socialist principles, suggesting a way to reshape economies in ways that are both sustainable and equitable.

Cooperative and Community Ownership: Promoting worker-owned cooperatives and community-owned enterprises can democratize economic power, provide secure employment, and reduce dependency on multinational corporations. Policies that support the establishment and growth of cooperatives—such as grants, tax incentives, and legal frameworks—could empower communities and workers, fostering a more equitable economic model. Cooperative ownership aligns with the principles of socialism, participatory economics, and other post-capitalist frameworks, as it places control over resources and decision-making in the hands of those directly affected by them.

Degrowth Initiatives and Resource Limits: Degrowth advocates argue that sustainable living requires a reduction in consumption and production to preserve environmental resources. Policies that limit resource extraction, reduce waste, and discourage consumerism align with this philosophy, challenging capitalism’s growth imperative. Implementing resource caps, banning planned obsolescence, and promoting circular economies are ways to move toward degrowth. By focusing on well-being over growth, societies can develop in harmony with environmental limits, creating resilient economies that prioritize quality of life over GDP.

Conclusion

The crises facing late-stage capitalism, from environmental degradation to rising inequality, indicate that the current system may be unable to meet the demands of a sustainable and equitable future. This article has explored how historical trends, economic theory, and modern realities converge to challenge the viability of capitalism, particularly in its advanced stage. The systemic issues identified—from monopolistic control and financialization to public welfare crises and ideological fractures—suggest that capitalism’s contradictions have reached a critical point. As capitalist structures falter, alternative models, such as socialism, eco-socialism, and participatory economics, provide valuable insights into what a post-capitalist world could look like.

While no single solution can resolve the complex issues embedded in capitalism, the policy proposals and case studies presented here demonstrate viable paths forward. Transitioning to a post-capitalist society will require not only economic restructuring but also a cultural shift that values collective well-being over individual profit. It will involve reclaiming the public sphere, fostering community ownership, and prioritizing environmental sustainability. Whether humanity can overcome the entrenched interests and power structures of capitalism remains uncertain. However, as the failures of late-stage capitalism become increasingly apparent, the call for transformative change grows louder. Only by reimagining our economic, political, and social systems can we hope to create a world that is just, equitable, and resilient in the face of global challenges.

This concludes the final chapter and brings the article’s exploration of late-stage capitalism and potential alternatives to completion. Please let me know if you'd like further expansion on any section, a bibliography, or additional refinements.

Bibliography

Albert, Michael. Parecon: Life After Capitalism. Verso, 2003.

Allen, Robert C. The Industrial Revolution: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press, 2017.

Aviles Espinoza, David Elias. "Unpacking Late Capitalism." University of Sydney News and Opinion. December 20, 2022. Available at: https://www.sydney.edu.au/news-opinion/news/2022/12/20/unpacking-late-capitalism.html​:contentReference[oaicite:0]{index=0}.

Braudel, Fernand. Civilization and Capitalism, 15th-18th Century. Harper & Row, 1981.

Chayka, Doug. "The Rise of the American Oligarchy." Mother Jones, January-February 2024 Issue.

Dutt, R. Palme. The Question of Fascism and Capitalist Decay. Workers' Library Publishers, New York, 1935. Available at Marxists Internet Archive: https://www.marxists.org/archive/dutt/articles/1935/question_of_fascism.htm​:contentReference[oaicite:2]{index=2}.

Hickel, Jason, and Sullivan, Dylan. "Capitalism and Extreme Poverty: A Global Analysis of Real Wages, Human Height, and Mortality Since the Long 16th Century." World Development, vol. 161, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.worlddev.2022.106026​:contentReference[oaicite:3]{index=3}.

Lenin, Vladimir Ilyich. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. Progress Publishers, Moscow, 1963. Available at Marxists Internet Archive: https://www.marxists.org/archive/lenin/works/1916/imp-hsc/​:contentReference[oaicite:4]{index=4}.

Mandel, Ernest. Late Capitalism. Verso, 1975.

Marx, Karl. Capital: A Critique of Political Economy. Volume I. Translated by Ben Fowkes. Penguin Classics, 1976.

Smith, Adam. The Wealth of Nations. W. Strahan and T. Cadell, 1776.

Sombart, Werner. Der Moderne Kapitalismus. Leipzig, 1927.

Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System I: Capitalist Agriculture and the Origins of the European World-Economy in the Sixteenth Century. Academic Press, 1974.